Exploration Tools

Tutorials

When faced with a binary with no source or parts of the source missing you can infer some of its functionalities based upon some basic reconnaissance techniques using various tools.

01. Tutorial - Poor Man's Technique: strings

The simplest recon technique is to dump the ASCII (or Unicode) text from a binary. It doesn't offer any guarantees but sometimes you can get a lot of useful information out of it.

By default, when applied to a binary it only scans the data section. To obtain information such as the compiler version used in producing the binary use:

strings -a crackme1

Let's illustrate how strings can be useful in a simple context.

Try out the crackme1 binary:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

int my_strcmp(char *s1, char *s2)

{

size_t i, len = strlen(s1);

if (len == 0)

return -1;

for (i = 0; i < len; i++)

if (s1[i] != s2[i])

return -1;

return 0;

}

int main()

{

char buf[1000];

printf("Password:\n");

if (fgets(buf, 1000, stdin) == NULL)

exit(-1);

buf[strlen(buf) - 1] = '\0';

if (!my_strcmp(buf, ???????????????????????)) {

printf("Correct!\n");

} else

printf("Nope!\n");

return 0;

}

The password has been redacted from the listing but you can retrieve it with strings.

Try it out!

02. Tutorial - Execution Tracing (ltrace and strace)

ltrace is an utility that can list library function calls or syscalls made by a program.

strace is similar, but only lists syscalls.

A syscall is a service exposed by the kernel itself.

The way they work is with the aid of a special syscall, called ptrace.

This single syscall forms the basis for most of the functionality provided by ltrace, strace, gdb and similar tools that debug programs.

It can receive up to 4 arguments: the operation, the PID to act on, the address to read/write and the data to write.

The functionality exposed by ptrace() is massive, but think of any functionality you've seen in a debugger:

- attach/detach to/from a process

- set breakpoints

- continue a stopped program

- read/write registers

- act on signals

- register syscalls

strace provides some pretty printing strictly concerning the syscalls of the traced process.

However, ltrace provides further functionality and gathers information about all library calls.

Here's how ltrace does its magic:

- it reads the

traceememory and parses it in order to find out about loaded symbols - it makes a copy of the binary code pertaining to a symbol using a

PTRACE_PEEKTEXTdirective ofptrace() - it injects a breakpoint using a

PTRACE_POKETEXTdirective ofptrace() - it listens for a

SIGTRAPwhich will be generated when the breakpoint is hit - when the breakpoint is hit, ltrace can examine the stack of the

traceeand print information such as function name, parameters, return codes, etc.

Let's try the next crackme.

If we remove my_strcmp from the previous crackme you can solve it even without strings because strcmp is called from libc.so.

You can use ltrace and see what functions are used and check for their given parameters.

Try it out on the second crackme where strings does not help (crackme2):

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

char correct_pass[] = ????????????????? ;

char *deobf(char *s)

{

???????????????

}

int main()

{

char buf[1000];

printf("Password:\n");

if (fgets(buf, 1000, stdin) == NULL)

exit(-1);

buf[strlen(buf) - 1] = '\0';

if (!strcmp(buf, deobf(correct_pass)))

printf("Correct!\n");

else

printf("Nope!\n");

return 0;

}

03. Tutorial - Symbols: nm

Symbols are basically tags/labels, either for functions or for variables. If you enable debugging symbols you will get information on all the variables defined but normally symbols are only defined for functions and global variables. When stripping binaries even these can be deleted without any effect on the binary behavior. Dynamic symbols, however, have to remain so that the linker knows what functions to import:

$ file xy

xy: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked (uses shared libs), for GNU/Linux 2.6.16, not stripped

$ nm xy

0804a020 B __bss_start

0804a018 D __data_start

0804a018 W data_start

0804a01c D __dso_handle

08049f0c d _DYNAMIC

0804a020 D _edata

0804a024 B _end

080484e4 T _fini

080484f8 R _fp_hw

0804a000 d _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_

w __gmon_start__

080482d4 T _init

08049f04 t __init_array_end

08049f00 t __init_array_start

080484fc R _IO_stdin_used

w _ITM_deregisterTMCloneTable

w _ITM_registerTMCloneTable

w _Jv_RegisterClasses

080484e0 T __libc_csu_fini

08048470 T __libc_csu_init

U __libc_start_main@@GLIBC_2.0

0804843c T main

U puts@@GLIBC_2.0

08048340 T _start

0804a020 D __TMC_END__

08048370 T __x86.get_pc_thunk.bx

$ strip xy

$ nm xy

nm: xy: no symbols

$ nm -D xy

w __gmon_start__

080484fc R _IO_stdin_used

U __libc_start_main

U puts

Let's take a look at another crackme that combines crackme1 and crackme2.

What would you do if you couldn't use neither strings nor ltrace to get anything useful?

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

char correct_pass[] = ????????????????????????

int my_strcmp(char *s1, char *s2)

{

size_t i, len = strlen(s1);

if (len == 0)

return -1;

for (i = 0; i < len; i++)

if (s1[i] != s2[i])

return -1;

return 0;

}

char *deobf(char *s)

{

???????????????????????????

}

int main()

{

char buf[1000];

deobf(correct_pass);

printf("Password:\n");

if (fgets(buf, 1000, stdin) == NULL)

exit(-1);

buf[strlen(buf) - 1] = '\0';

if (!my_strcmp(buf, correct_pass)) {

printf("Correct!\n");

} else

printf("Nope!\n");

return 0;

}

In crackme3, deobfuscation is done before the password is read.

Since the correct_pass has an associated symbol that is stored at a known location you can obtain the address and peer into it at runtime:

$ nm crackme3 | grep pass

0804a02c D correct_pass

$ gdb -n ./crackme3

Reading symbols from ./crackme3...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

(gdb) run

Password:

^C

Program received signal SIGINT, Interrupt.

0xf7fdb430 in __kernel_vsyscall ()

(gdb) x/s 0x0804a02c

0x804a02c <correct_pass>: "JWxb7gE2pjiY3gRG8U"

The above x/s 0x0804a02c command in GDB is used for printing the string starting from address 0x0804a02c.

x stands for examine memory and s stands for string format.

In short it dumps memory in string format starting from the address passed as argument.

You may print multiple strings by prefixing s with a number, for example x/20s 0x0804a02c.

For other programs (that are not stripped) you can even get a hint as to what they do using solely nm:

$ nm mystery_binary

.....

0000000000402bef T drop_privs(char const*)

00000000004027db T IndexHandler(std::string const&, HttpRequest const&, HttpResponse*)

0000000000402ad8 T StatusHandler(std::string const&, HttpRequest const&, HttpResponse*)

000000000040237f T NotFoundHandler(std::string const&, HttpRequest const&, HttpResponse*)

00000000004024a1 T BadRequestHandler(std::string const&, HttpRequest const&, HttpResponse*)

00000000004025c3 T MaybeAddCORSHeader(std::string const&, HttpRequest const&, HttpResponse*)

0000000000402f52 t __static_initialization_and_destruction_0(int, int)

0000000000402cf8 T handle(int)

00000000004020fc T recvlen(int, char*, unsigned long)

0000000000402195 T sendlen(int, char const*, unsigned long)

0000000000402224 T sendstr(int, char const*)

0000000000402255 T urldecode(std::string const&)

.....

Note: In this case the signatures are also decoded because the binary was compiled from C++ source code.

Dealing with stripped binaries (or worse, statically linked binaries that have been stripped) is harder but can still be done. We'll see how in a future lab.

04. Tutorial - Library Dependencies

Most programs you will see make use of existing functionality. You don't want to always reimplement string functions or file functions. Therefore, most programs use dynamic libraries. These shared objects, as they are called alternatively, allow you to have a smaller program and also allow multiple programs to use a single copy of the code within the library. But how does that actually work?

What makes all of these programs work is the Linux dynamic linker/loader. This is a statically linked helper program that resolves symbol names from shared objects at runtime. We can use the dynamic linker to gather information about an executable.

The first and most common thing to do is see what libraries the executable loads, with the ldd utility:

$ ldd /bin/ls

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffff13fe000)

librt.so.1 => /lib64/librt.so.1 (0x00007fc9b4893000)

libacl.so.1 => /lib64/libacl.so.1 (0x00007fc9b468a000)

libc.so.6 => /lib64/libc.so.6 (0x00007fc9b42da000)

libpthread.so.0 => /lib64/libpthread.so.0 (0x00007fc9b40bd000)

libattr.so.1 => /lib64/libattr.so.1 (0x00007fc9b3eb8000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007fc9b4a9b000)

We see that for each dependency in the executable, ldd lists where it is found on the filesystem and where it is loaded in the process memory space.

Alternatively, you can achieve the same result with the LD_TRACE_LOADED_OBJECTS environment variable, or with the dynamic loader itself:

$ LD_TRACE_LOADED_OBJECTS=whatever /bin/ls

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007fff325fe000)

librt.so.1 => /lib64/librt.so.1 (0x00007f1845386000)

libacl.so.1 => /lib64/libacl.so.1 (0x00007f184517d000)

libc.so.6 => /lib64/libc.so.6 (0x00007f1844dcd000)

libpthread.so.0 => /lib64/libpthread.so.0 (0x00007f1844bb0000)

libattr.so.1 => /lib64/libattr.so.1 (0x00007f18449ab000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f184558e000)

$ /lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 --list /bin/ls

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007fff1e712000)

librt.so.1 => /lib64/librt.so.1 (0x00007f18a07d8000)

libacl.so.1 => /lib64/libacl.so.1 (0x00007f18a05cf000)

libc.so.6 => /lib64/libc.so.6 (0x00007f18a021e000)

libattr.so.1 => /lib64/libattr.so.1 (0x00007f189fdfc000)

libpthread.so.0 => /lib64/libpthread.so.0 (0x00007f18a0001000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 => /lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f18a0c44000)

When using the loader directly, make sure the loader and the executable are compiled for the same platform (e.g. they are both 64-bit or 32-bit). You may find out more information about dynamic linker/loader variables in its man page. Issue the command:

man ld-linux.so

and search for the LD_ string to find variables information.

ldd shows us which libraries are loaded, but it's not any clearer how the loader knows where to load them from.

First of all, the loader checks every dependency for a slash character.

If it finds such a dependency it loads the library from that path, whether it is a relative of absolute path.

But it is not the case in our example.

For dependencies without slashes, the search order is as follows:

DT_RPATHattribute in the.dynamicsection of the executable, provided there is noDT_RUNPATH; this is deprecatedLD_LIBRARY_PATHenvironment variable, which is similar toPATH; does not work withsetuid/setgidprogramsDT_RUNPATHattribute in the.dynamicsection of the executable/etc/ld.so.cache, generated byldconfig/liband then/usr/lib

The last two options are skipped if the program was linked with the -z nodeflib option.

Now let's see exactly where the loader finds the libraries:

$ LD_DEBUG=libs /bin/ls

11451: find library=librt.so.1 [0]; searching

11451: search cache=/etc/ld.so.cache

11451: trying file=/lib64/librt.so.1

11451:

11451: find library=libacl.so.1 [0]; searching

11451: search cache=/etc/ld.so.cache

11451: trying file=/lib64/libacl.so.1

11451:

11451: find library=libc.so.6 [0]; searching

11451: search cache=/etc/ld.so.cache

11451: trying file=/lib64/libc.so.6

11451:

11451: find library=libpthread.so.0 [0]; searching

11451: search cache=/etc/ld.so.cache

11451: trying file=/lib64/libpthread.so.0

11451:

11451: find library=libattr.so.1 [0]; searching

11451: search cache=/etc/ld.so.cache

11451: trying file=/lib64/libattr.so.1

The LD_DEBUG environment variable makes the dynamic loader be verbose about what it's doing.

Try LD_DEBUG=help if you're curious about what else you can find out.

We can see in the output listed above that all the libraries are found via the loader cache.

The number at the beginning of each line is the PID of the ls process.

And now we can discuss how the loader resolves symbols after it has found the libraries containing them. While variables are resolved when the library is opened, that is not the case for function references. When dealing with functions, the Linux dynamic loader uses something called lazy binding, which means that a function symbol in the library is not resolved until the very first call to it. Think about why this difference exists.

You can see the way lazy binding behaves:

$ LD_DEBUG=symbols,bindings ./crackme2

...

11480: initialize program: ./crackme2

11480:

11480:

11480: transferring control: ./crackme2

11480:

11480: symbol=puts; lookup in file=./crackme2 [0]

11480: symbol=puts; lookup in file=/lib32/libc.so.6 [0]

11480: binding file ./crackme2 [0] to /lib32/libc.so.6 [0]: normal symbol 'puts' [GLIBC_2.0]

Password:

11480: symbol=fgets; lookup in file=./crackme2 [0]

11480: symbol=fgets; lookup in file=/lib32/libc.so.6 [0]

11480: binding file ./crackme2 [0] to /lib32/libc.so.6 [0]: normal symbol 'fgets' [GLIBC_2.0]

I_pity_da_fool_who_gets_here_without_solving_crackme2

11480: symbol=strlen; lookup in file=./crackme2 [0]

11480: symbol=strlen; lookup in file=/lib32/libc.so.6 [0]

11480: binding file ./crackme2 [0] to /lib32/libc.so.6 [0]: normal symbol 'strlen' [GLIBC_2.0]

11480: symbol=strcmp; lookup in file=./crackme2 [0]

11480: symbol=strcmp; lookup in file=/lib32/libc.so.6 [0]

11480: binding file ./crackme2 [0] to /lib32/libc.so.6 [0]: normal symbol 'strcmp' [GLIBC_2.0]

Nope!

11480:

11480: calling fini: ./crackme2 [0]

11480:

As you can see, functions like puts(), fgets(), strlen() and strcmp() are not actually resolved until the first call to them is made.

Make the loader resolve all the symbols at startup.

(Hint: ld-linux).

Library Wrapper Task

You've previously solved crackme2 with the help of the ltrace.

Check out the files from 04-tutorial-library-dependencies.

The folder consists of a Makefile and a C source code file reimplementing the strcmp() function (library wrapper).

The strcmp.c implementation uses LD_PRELOAD to wrap the actual strcmp() call to our own.

In order to see how that works, we need to create a shared library and pass it as an argument to LD_PRELOAD.

The Makefile already takes care of this.

To build and run the entire thing, simply run:

make run

This will build the shared library file (strcmp.so) and run the crackme2 executable under LD_PRELOAD.

Our goal is to use the strcmp() wrapper to alter the program behavior.

We have two ways to make the crackme2 program behave our way:

- Leak the password in the

strcmp()wrapper. - Pass the check regardless of what password we provide.

Modify the strcmp() function in the strcmp.c source code file to alter the crackme2 program behavior in each of the two ways shown above.

To test it, use the Makefile:

make run

05. Tutorial - Network: netstat and netcat

Services running on remote machines offer a gateway to those particular machines.

Whether it's improper handling of the data received from clients, or a flaw in the protocol used between server and clients, certain privileges can be obtained if care is not taken.

We'll explore some tools and approaches to analyzing remote services.

To follow along, use the server and client programs from 05-tutorial-network-netstat-netcat.

First of all, start the server:

$ ./server

Welcome to the awesome server.

Valid commands are:

quit

status

Running any of them at this point doesn't offer much help. We'll come back to this later.

The most straightforward way to see what a server does is the netstat utility.

$ netstat -tlpn

(Not all processes could be identified, non-owned process info

will not be shown, you would have to be root to see it all.)

Active Internet connections (only servers)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State PID/Program name

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:36732 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 3062/steam

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:57343 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 3062/steam

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:31337 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 15022/./server

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:58154 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 3062/steam

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:60783 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 2644/SpiderOak

tcp 0 0 192.168.101.1:53 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN -

tcp 0 0 192.168.100.1:53 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN -

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:44790 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 2644/SpiderOak

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:631 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN -

tcp6 0 0 :::631 :::* LISTEN -

Here we're looking at all the programs that are listening (-l) on a TCP port (-t).

We're also telling netcat not to resolve hosts (-n) and to show the process that is listening (-p).

We can see that our server is listening on port 31337.

Let's keep that in mind and see how the client behaves:

$ ./client

Usage: ./client <client name> <server IP> <server port>

$ ./client the_laughing_man localhost 31337

Welcome to the awesome server.

Valid commands are:

listclients

infoclient <client name> [ADMIN access required]

name, IP, port, privileged, connected time

sendmsg <client name> <message>

Enter a command (or 'quit' to exit):

listclients

Connected clients are:

the_laughing_man

Enter a command (or 'quit' to exit):

sendmsg the_laughing_man test

Enter a command (or 'quit' to exit):

Message from the_laughing_man

test

Enter a command (or 'quit' to exit):

infoclient the_laughing_man

Not enough minerals!

Enter a command (or 'quit' to exit):

So we can do anything except the privileged command infoclient.

Running status on the server yields no information.

What can we do now?

We can see what the server and client are exchanging at an application level by capturing the traffic with the tcpdump utility.

Start tcpdump, the server and then the client, and run the commands again.

When you're done, stop tcpdump with Ctrl+C.

# tcpdump -i any -w crackme5.pcap 'port 31337'

tcpdump: listening on any, link-type LINUX_SLL (Linux cooked), capture size 65535 bytes

^C21 packets captured

42 packets received by filter

0 packets dropped by kernel

Here we're telling tcpdump to listen on all available interfaces, write the capture to the crackme5.pcap file and only log packets that have the source or destination port equal to 31337.

We can then open our capture with Wireshark in order to analyze the packets in a friendlier manner.

You can look at the packets exchanged between server and client.

Notice that there seems to be some sort of protocol where values are delimited by the pipe character.

What is especially interesting is the first data packet sent from the client to the server, which sends the_laughing_man|false.

While we've specified the client name, there was nothing we could specify via the client command-line in order to control the second value.

However, since this seems to be a plain text protocol, there is an alternative course of action available.

The netcat utility allows for arbitrary clients and servers.

It just needs a server address and a server port in client mode.

We can use it instead of the "official" client and see what happens when we craft the first message.

Go ahead!

Start the server again and a normal client.

Connect to the server using netcat.

Then send out the required string through the netcat connection with true as the second parameter and see if you can find out anything about the normal client.

# netcat localhost 31337

Welcome to the awesome server.

Valid commands are:

listclients

infoclient <client name> [ADMIN access required]

name, IP, port, privileged, connected time

sendmsg <client name> <message>

Doing it in Python

You can create a sever and a client in Python only.

We can use the server.py and client.py scripts.

Check them out first.

Then run the server by using:

python server.py

It now accepts connections on TCP port 9999 as you can see by using netstat:

$ netstat -tlpn

[...]

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State PID/Program name

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:9999 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 12541/python

[...]

Now you can test it using the Python client:

$ python client.py

sending 'anaaremere'

received 'ANAAREMERE'

We can do the same using netcat as the client:

$ nc localhost 9999

anaaremere

ANAAREMERE

Doing it Only with netcat

We can still simulate a network connection using netcat only, both for starting the server and for running the client.

Start the server with:

nc -l -p 4444

Now run the client and send messages by writing them to standard input:

$ nc localhost 4444

aaaaa

bbbbb

Messages you write to the client and up in the server.

This goes both ways: if you write messages on the server they end up in the client. Try that.

If you want to send a large chunk of data you can redirect a file. Start the server again:

nc -l -p 4444

and now send the file to it:

cat /etc/services | nc localhost 4444

It's now on the server-side.

You can also do it with UDP, instead of TCP by using the -u flag both for the server and the client.

Start the server using:

nc -u -l -p 4444

And run the client using:

cat /etc/services | nc -u localhost 4444

That's how we use netcat (the network swiss army knife).

You can also look into socat for a complex tool on dealing with sockets.

06. Tutorial - Open files

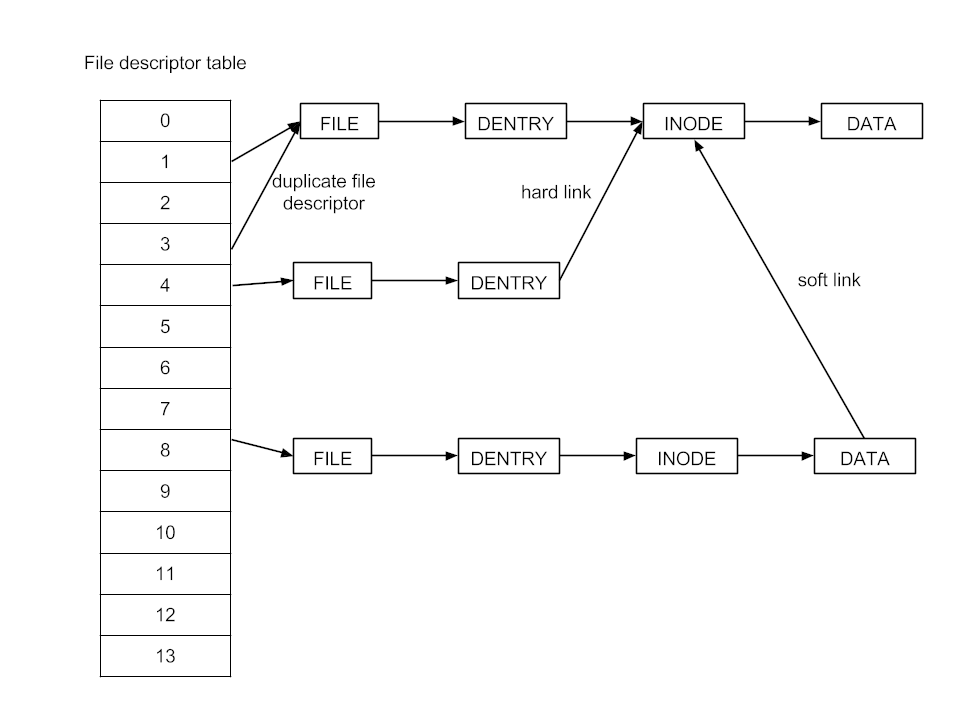

Let's remember how files and programs relate in Linux.

Let's also remember that, in Linux, file can mean one of many things:

- regular file

- directory

- block device

- character device

- named pipe

- symbolic or hard link

- socket

Let's look at the previous server from crackme5.

Start it up once again.

While previously we've used netstat to gather information about it, that was by no means the only solution.

lsof is a tool that can show us what files a process has opened:

$ lsof -c server

COMMAND PID USER FD TYPE DEVICE SIZE/OFF NODE NAME

server 9678 amadan cwd DIR 8,6 4096 1482770 /home/amadan/projects/sss/session01/crackmes/crackme5

server 9678 amadan rtd DIR 8,6 4096 2 /

server 9678 amadan txt REG 8,6 17524 1442625 /home/amadan/projects/sss/session01/crackmes/crackme5/server

server 9678 amadan mem REG 8,6 1753240 3039007 /lib64/libc-2.17.so

server 9678 amadan mem REG 8,6 88088 3039019 /lib64/libnsl-2.17.so

server 9678 amadan mem REG 8,6 144920 3038998 /lib64/ld-2.17.so

server 9678 amadan 0u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2

server 9678 amadan 1u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2

server 9678 amadan 2u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2

server 9678 amadan 3u IPv4 821076 0t0 TCP *:31337 (LISTEN)

We can see the standard file descriptors found in any process, as well as our socket.

- The

FDcolumn shows the file descriptor entry for a file, or a role in case of special files. We notice the current working directory (cwd), the root directory (rtd), the current executable (txt), some memory mapped files (mem) and the file descriptors (0-3). For normal file descriptors,rmeans read access,wmeans write access andumeans both. - The

TYPEcolumn shows whether we're dealing with a directory (DIR), a regular file (REG), a character device (CHR), a socket (IPv4) or other type of file. - The

NODEcolumn shows the inode of the file, or a class marker as is the case for the socket. - The

NAMEcolumn shows the path to the file, or the bound address and port for a socket.

We've left out some details since they are not relevant for our purposes. Feel free to read the manual page.

You could also get some hint that there is an open socket by looking into the /proc virtual filesystem:

$ ls -l /proc/`pidof server`/fd

total 0

lrwx------ 1 amadan amadan 64 Jun 15 22:04 0 -> /dev/pts/2

lrwx------ 1 amadan amadan 64 Jun 15 22:04 1 -> /dev/pts/2

lrwx------ 1 amadan amadan 64 Jun 15 22:03 2 -> /dev/pts/2

lrwx------ 1 amadan amadan 64 Jun 15 22:04 3 -> socket:[883625]

We'll be using crackme6 for the next part of this section.

Try the conventional means of strings and ltrace on it.

Then run it normally:

$ ./crackme6

Type 'start' to begin authentication test

Before complying to what the program tells us, let's use lsof to see what we can find out:

$ lsof -c crackme6

COMMAND PID USER FD TYPE DEVICE SIZE/OFF NODE NAME

crackme6 10466 amadan cwd DIR 8,6 4096 1482769 /home/amadan/projects/sss/session01/06-tutorial-open-files

crackme6 10466 amadan rtd DIR 8,6 4096 2 /

crackme6 10466 amadan txt REG 8,6 12922 5377126 /home/amadan/projects/sss/session01/06-tutorial-open-files/crackme6

crackme6 10466 amadan mem REG 8,6 1753240 3039007 /lib64/libc-2.17.so

crackme6 10466 amadan mem REG 8,6 100680 3039039 /lib64/libpthread-2.17.so

crackme6 10466 amadan mem REG 8,6 144920 3038998 /lib64/ld-2.17.so

crackme6 10466 amadan 0u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2

crackme6 10466 amadan 1u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2

crackme6 10466 amadan 2u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2

crackme6 10466 amadan 3w FIFO 0,32 0t0 988920 /tmp/crackme6.fifo

crackme6 10466 amadan 4r FIFO 0,32 0t0 988920 /tmp/crackme6.fifo

There seems to be a named pipe used by the executable. Let's look at it:

more /tmp/crackme6.fifo

Now go back again at the crackme6 console and type start.

If you see the message that the authentication test has succeeded, quit and try again.

If you do not see the message, kill the crackme6 process, look at the more command output and then delete the pipe file.

Now try the password.

Misc

There are other sources of information available about running processes if you prefer to do things by hand such as:

/proc/<PID>/environ: all environment variables given when the process was started/proc/<PID>/fd: opened file descriptors./proc/<PID>/mem: address space layout/proc/<PID>/cwd: symlink to working directory/proc/<PID>/exe: symlink to binary image/proc/<PID>/cmdline: complete program command-line, with arguments

Challenges

Challenges can be found in the activities/<CHALLENGE_NUMBER>-challenge-<CHALLENGE_NAME> directory.

07. Challenge - Perfect Answer

For this task use the perfect binary.

Can you find the flag?

08. Challenge - Lots of strings

Use the lots_of_strings binary.

Can you find the password?

Hint: use the tools presented in the tutorials.

09. Challenge - Sleepy cats

For this task use the sleepy binary.

The sleep() function takes too much.

Ain't nobody got time for that.

We want the flag NOW!

Modify the binary in order to get the flag.

To edit a binary, you can use vim + xxd or Bless.

We strongly encourage you to use Bless

10. Challenge - Hidden

For this challenge use the hidden binary.

Can you find the hidden flag?

You could use ltrace and strace to find the flag.

But try to make it give you the flag by simply altering the environment, do not attach to the executable.

11. Challenge - Detective

This challenge runs remotely at 141.85.224.104:31337.

You can use netcat to connect to it.

Investigate the detective binary.

See what it does and work to get the flag.

You can start from the sol/exploit_template.py solution template script.

There is a bonus to this challenge and you will be able to find another flag. See that below.

Bonus: Get the Second Flag

You can actually exploit the remote detective executable and get the second flag.

Look thoroughly through the executable and craft your payload to exploit the remote service.

You need to keep the connection going.

Use the construction: cat /path/to/file - | nc <host> <port>

Extra

If you want some more, have a go at the bonus task.

It is a simplified CTF task that you should be able to solve using the information learned in this lab.

Hint: This executable needs elevated permissions (run with sudo).

Further pwning

pwnable.kr is a wargames site with fun challenges of different difficulty levels.

After completing all tutorials and challenges in this session, you should be able to go there and try your hand at the following games from Toddler's bottle: fd, collision, bof, passcode, mistake, cmd1, blukat (of course, you are encouraged to try any other challenges, but they might get frustrating, as they require knowledge of notions we will explore in future sessions).